Memoirs of a Shattered Soul — 13: Prisoners of War

Marilyn said wryly, "That's the whole paradox of life, Yukiko. It makes sense, but it makes no sense."

July 8, 2013

Last month my father helped Marilyn get things ready for Mr. Hauser’s release from the hospital in Interlaken. We knew that he would not be returning to the residence where he was living before. Instead he is now staying at l’Oasis in Lauterbrunnen, with medically trained caregivers hired to attend to his needs. He seems more fragile now, and even more forgetful than before.

No one lives forever, Yukiko. Not even concentration camp survivors or musical virtuosos.

For me, obviously, his move to Lauterbrunnen means that I can see him more often. I don’t visit every day, but I come whenever I can, sometimes for an hour to play music for him or sometimes just for a few minutes to say hello.

Marilyn has stopped introducing me every time. Mr. Hauser seems to have accepted the fact that his life is now filled with people whose names and faces he cannot remember. Also, I noticed that he no longer asks if he can play my violin. I wonder, does that mean he remembers something about the accident? Perhaps unconsciously he worries that he might harm my instrument again.

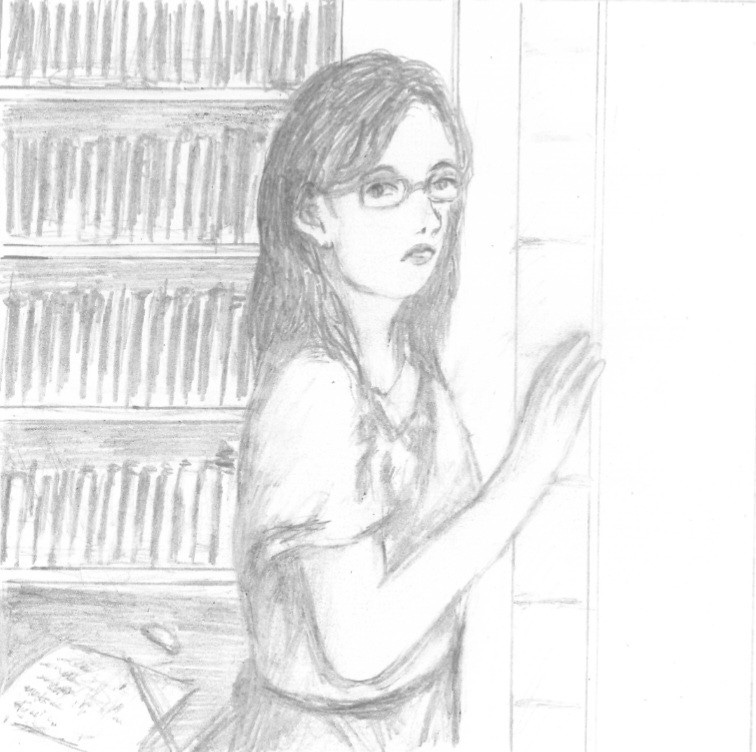

I visited him today. After the visit, I was standing at the window in the vast library, beside the painting of the white fox, when Marilyn came to find me. We both sat down at a table.

“How are you feeling, Yukiko?” she asked me.

This was not a casual question. In Western culture, it’s common for people to greet each other this way and then politely lie, saying, “I’m fine.” However, this was not what Marilyn was asking me.

“I feel confused and helpless, Marilyn-san,” I said. “I feel as though everything I love is threatened by things I cannot understand. Some days are better than others, but the confusion never really goes away.”

Marilyn nodded, her blue eyes full of sympathy. “Your father said he was talking to you about your grandfather. He said you might have questions for me.”

I looked again at the painting of the white fox. I couldn’t look her in the eyes directly: somehow it seemed impolite.

“I have questions, but not about my grandfather exactly. What my father told me surprised me, but then I realised I shouldn’t be surprised. I knew my grandfather was a genetic researcher. And I knew that Japan was cooperating with Germany during the war. It makes sense that the Germans would be interested in funding his work. It makes sense, but… at the same time it makes no sense.”

Marilyn said wryly, “That’s the whole paradox of life, Yukiko. It makes sense, but it makes no sense.”

“So I have questions, but they’re too big for me to expect you to answer them. Why was Japan cooperating with Germany? And why was there a war in the first place? And why were innocent people like Mr. Hauser or your mother made into prisoners of war and treated as though they were less than human? Those are the kind of questions I ask myself.”

Marilyn put her hand on my cheek, gently. “Why is there evil in this world? That’s a hard question.”

“And it doesn’t stop there,” I said. “When my mother was attacked and left in a coma, I was so angry at the man who did that to her. I wanted to kill him. It seemed so unfair that someone could walk into our house on the lake, just walk past all our defenses, and cause us so much hurt. But that’s also part of life, isn’t it? The casual violence of it. You can’t stop an earthquake or a tsunami. You can’t stop cats from fighting on the street. You can’t stop cherry blossoms falling or noble samurai dying…”

Marilyn did not answer this time. We sat side by side, not looking at each other directly, pondering all my unanswerable questions.

Finally Marilyn said, “Yukiko, do you know that poem by Kobayashi Issa, ‘Everything I touch?’”

It was a rhetorical question. Of course I knew it. Every schoolchild in Japan has to learn this haiku:

My old village home

Everything I touch in you

Turns into a thorn. "I think this is something like what you're feeling now," Marilyn told me. "It's what every sensitive soul in this world feels at some time or other. Life can seem senseless and cruel. Everywhere you turn there is pain. You wish you could make it go away, but you can't."

I nodded. I didn't feel like arguing with Kobayashi Issa, and in any case, in this matter I completely agreed with him.

"You can't stop the pain, but you can learn to see beyond it, Yukiko," Marilyn said. "There is goodness and beauty in the universe too. Anne Frank was in Auschwitz and wrote in her diary, 'I don't think of all the misery, but of the beauty that still remains.'"

"And then the Nazis killed her," I said.

"They killed her body, but not her soul. Not her spirit. Also, do you know where Abelard first heard and fell in love with classical music? It was also there in Auschwitz. They had an orchestra made from prisoners who were musicians. That was where Abelard first heard Massenet's 'Meditation' and Vivaldi's 'Four Seasons.'"

"He shouldn't have heard it in a place like that, where soldiers tattooed numbers on his arm and his whole family was murdered," I said.

Marilyn nodded. "You're right, Yukiko, but he did. It didn't take away the pain, but it made it somehow bearable. My mother always told me: The real prisoners of war are the ones who become bitter, the ones who can never let go. They're prisoners all their lives. Think about that, Yukiko. Sometimes when you're in pain, remember it.

I closed my eyes and didn't answer, but I knew I would think about it. What she said made no sense, but... at the same time it seemed like the only sane thing I'd ever heard.

You’re reading: Memoirs of a Shattered Soul