Memoirs of a Shattered Soul — 06: The Forgetful Wizard

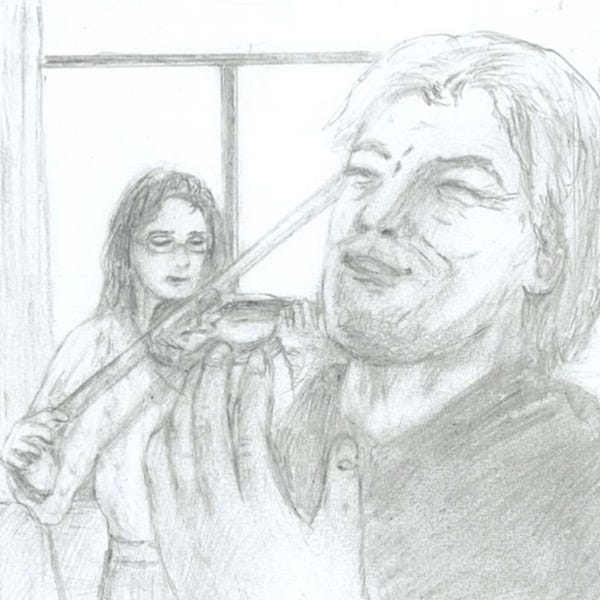

I opened my violin case and started playing for this man who was losing his memory, who once conducted one of the most prestigious orchestras in the world.

April 2, 2013

I first started learning to play the violin when I was five years old. I actually have no clear memory of a time in my life when I wasn’t playing the violin. It was my mother’s wish for me, something that she had always wanted to learn herself but never did. She had studied to play the piano a bit in middle school, but ironically after her singing career catapulted her to fame she never had the time to pursue classical piano any further.

I have cherished memories of all the times that we used to play music together. When I was five we played variations of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.” Eventually we could play Japanese pop music, including her own greatest hits, or songs from Miyazaki films like “My Neighbour Totoro” or “Princess Mononoko.”

At a certain point I started learning more difficult classical pieces on the violin that she couldn’t really play on the piano. She would just sit and listen to me, with amazement in her eyes and a beatific smile on her face.

Aside from my mother, though, and the people who came to my recitals, there are not many others who have heard me play the violin. My parents, both burdened by fame, never pushed me to seek attention for myself. They always cautioned me to be patient. “If you are in a hurry, go the long way around,” as the saying goes.

So when Marilyn DeZeuw asked me if I would like to visit a friend of hers and play the violin for him, I was genuinely surprised.

Marilyn’s friend, Abelard Hauser, lives in Interlaken, a short train ride away from Lauterbrunnen. He is a patient in a centre that cares for a number of elderly residents. Marilyn told me, “Abelard is a composer and was once also the conductor of the Berlin Philharmoniker Orchestra. He’s seventy-five years old and one of the sweetest men I’ve ever met… but now he’s losing his memory. He has Alzheimer’s.”

I felt a bit confused. “But you want me to play music for him? You think that will do him good?”

A dreamy look came into Marilyn’s deep blue eyes. “Yes, Yukiko-chan. Music is good for him. Listening to classical music is like magic. It brings back a little bit of who he was before…”

That was the conversation we had yesterday. So today I followed Marilyn to Interlaken, bringing my violin, wondering if I would really be able to perform magic with it.

When we arrived at the centre in Interlaken, a kindly nurse led us to Abelard Hauser’s room. The room was neat and beautifully arranged, but mostly lacking in the things that make a room feel as though somebody lives there, the accumulated bric-à-brac of a life. There were only a few photos on the window sill, showing Mr. Hauser as a younger man in his glory years, including one with the orchestra in Berlin.

“Hello Abelard,” Marilyn said simply, with a smile. “This is Yukiko. She’s visiting me now from Japan. Can she play some music for you?”

And with that rather innocuous introduction, I opened my violin case and started playing for this man who once conducted one of the most prestigious orchestras in the world.

Marilyn had said that I could play whatever I wanted, so I did. I played “Yuki No Kessho” and other songs my mother had sung in her illustrious career. I played movie music by Joe Hisaishi, Ennio Morricone, John Williams. I noticed a sad look in Mr. Hauser’s eyes when I was playing the theme from “Schindler’s List.” Then when I got to “Meditation” from the opera Thaïs, he stopped me.

“Do you know the story behind that song?” he asked. “What was happening in the opera when the song was played?”

I shook my head. My violin teacher never told me anything about that.

“There was a monk named Athanaël who had fallen in love with a beautiful woman named Thaïs. She was a courtesan, and he wanted to convert her to Christianity… but his motives were not pure. In fact, his desire was to marry her and give up his life as a monk. The meditation is where Thaïs is thinking over what Athanaël told her, and she chooses to follow God. She decides to give up everything and become a nun.”

As he said this last part, he looked at Marilyn in a way that was hard for me to understand. I thought that she might blush, but she just kept smiling sweetly.

Then Mr. Hauser really surprised me. “Can I play your violin?” he asked.

With my consent, Mr. Hauser took the violin from my hands, raised the bow and started to play. It was the same song I had been playing, “Meditation,” but somehow it sounded about a thousand times better.

I talked about mushin, and how it applies to martial arts. It also applies to music. A musician can become so proficient that his or her hands move without thinking and the music comes out perfectly. I cannot claim that I’ve ever achieved that level of mastery, but as I listened to Mr. Hauser with my violin, I truly believed that it was magic and that he was some kind of wizard.

On the train ride back to Lauterbrunnen, Marilyn thanked me for coming with her and playing my violin for Mr. Hauser. Still moved by what I had heard, I told her: “I wouldn’t have missed that experience for anything in the world.”

You’re reading: Memoirs of a Shattered Soul